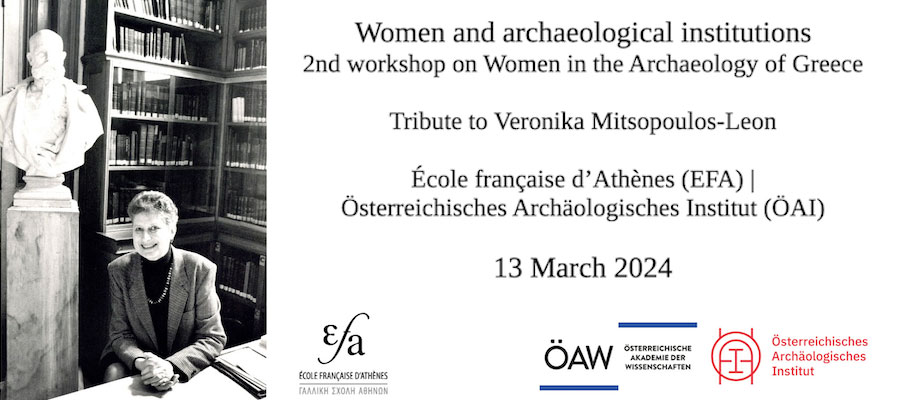

Women and Archaeological Institutions, 2nd workshop on Women in the Archaeology of Greece, Athens. March 13, 2024

The 2024 workshop on Women in the Archaeology of Greece will focus on the role played by institutions such as the Archaeological Service, universities, research centers and foreign schools in women’s career developments. It will be held in honor of the exceptional achievements of Veronika Mitsopoulos-Leon (1936-2023), the director of the Austrian Archaeological Institute at Athens from 1964 until 2001.

The papers presented in the 2023 workshop drew attention to different modes of inclusion and exclusion of women pioneers, while revealing that these women responded in a myriad of different ways to the obstacles they encountered. Such dynamics are especially evident in institutional frameworks. At the beginning of the 20th century, several foreign archaeological institutes opened their doors to women, albeit with some restrictions. It was, for instance, the case of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, which welcomed female students already in the late 19th century, while however banning them from excavation projects at first, before confining them to the management of storerooms and the study of small finds – i.e. the depreciated ‘archaeological housework’. At the Italian Archaeological School at Athens, as was also the case at ASCSA, restrictions on travel and fieldwork resulted more from implicit practices than explicit rules, which added to the uncertainty and the vulnerability of young female researchers who could not anticipate their superiors’ reaction.

Other institutions, such as the École française d'Athènes, were long opposed to women’s participation in excavations and to their recruitment as researchers. Indeed, it is only in 1956 that EFA welcomed its first French female scientific member and, although women members increasingly grew in number starting from the 1970s, parity was not achieved until the 1990.

In parallel, some Greek female archaeologists managed to benefit from their assignment to the ‘archaeological housework’ by taking charge of national collections. However, their position proved to be precarious in the face of political events, as a law enacted by the dictatorial regime of the 4th of August prohibited women from joining the Archaeological Service from 1939 until 1955. In contrast, in Poland, the post-war communist ideology enabled women to more easily access academic positions. National and regional political conditions evidently affected women pioneer archaeologists in drastically different ways. However, all of them shared similar struggles in combining private and professional life; some therefore gave up fieldwork after marriage, while others opted for a non-conformist lifestyle that exposed them to violent criticisms on the part of their male colleagues.

Ultimately, the integration of women into archaeological institutions in Greece during the first half of the 20th century owed a lot to their audacity, their tenacity and their resilience. The following generations of women faced less explicit discriminations to enter foreign institutes (after World War II) and the Greek Archaeological Service (especially from the 1980s onwards), but it cannot be denied that this ‘feminization of archaeology’ over the last four decades is also related to the loss of prestige of the discipline and the limited economic stability it offers. Careers in the Archaeological Service, in particular, require great dedication and self-sacrifice, whereas Greek academia remains predominantly male, even though an increasing number of women are breaking through.

The 2024 workshop on Women in the Archaeology of Greece aims to explore these different aspects of the institutional obstacles and opportunities encountered by women, in particular:

- the official or unofficial reluctance towards women on the part of foreign institutes and Greek universities, Archaeological Services, museums and research centers;

- the role of these institutions as springboards or, on the contrary, brakes in the career of women archaeologists, for instance in terms of funding opportunities;

- the strategies adopted by women to pursue their career goals

We welcome proposals for communications in Greek, English, French or German.