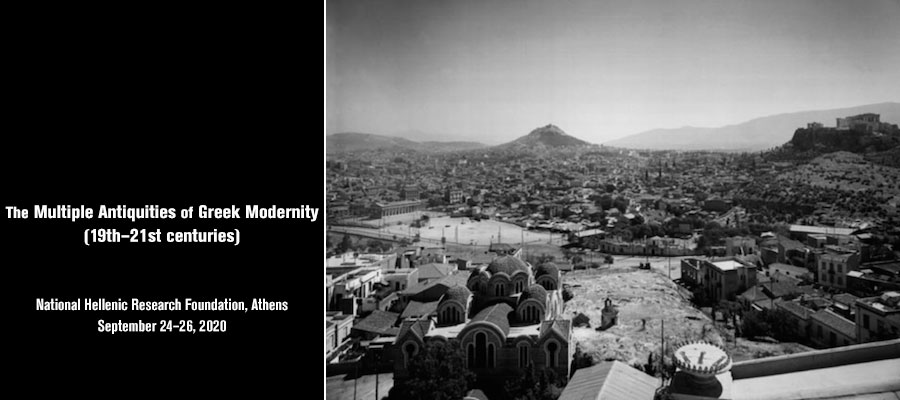

The Multiple Antiquities of Greek Modernity (19th–21st centuries), National Hellenic Research Foundation, Athens, September 24–26, 2020

“Wishing to restore to life a nation that has disappeared from history as a political entity on account of its former glory is as reasonable as wishing to resuscitate animal species that have ceased to exist long ago and whose traces are buried in the Paleozoic layers of the earth (…) and yet it is this kind of absurd thinking that has taken hold of those of us who seek to found our national existence not on the development of existing elements but on memories of classical antiquity – which, by the way, modern Greeks have a very poor knowledge of, acquired via a second-rate translation by A.R. Rangavis of the Compendium of Goldsmith’s History of Greece.”

Ἀσμοδαῖος, 22/2/1881

National origins were at the centre of discussions across Europe in the nineteenth century. Could it have been possible, then, for the Greeks not to take advantage of a source of legitimacy as flattering and as promising as antiquity? In fact, ancient Greece turned right away into a decisive factor in the arduous process of shaping Modern Greek identity and state ideology. The mode of connection established in this manner between the Modern Greek state and the ancient Greek past has nevertheless proved to be an incessant source of genuine difficulties as illustrated by this (self-) critical description of the Modern Greek obsession with antiquity which was published anonymously in 1881 in the satirical journal of Themos Anninos, Asmodaios.

The attempted large-scale resuscitation of an irrevocably bygone age ended up being a crushing weight upon the present of a society in which the recollection of antiquity had to be actively cultivated. The gap that emerged between the spoken (δημοτική) and the purist (καθαρεύουσα) language highlights the grip that a monumental past had on a present that was destined to become archaizing. At the same time, a return to antiquity of such scope depended upon the successful introduction and adaptation of the classical tradition of Western Europe and its academic know-how.

We aim to examine the Modern Greek turn to the Ancient Greek past, giving particular attention to:

- The diversity and multiplicity of the “Antiquities” created and disseminated in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries

- The contexts – national, cultural, political – in which diverse and often conflicting conceptions of antiquity were formulated and interacted with each other

- The ways in which the dominant version of national history was sustained or undermined by co-existing versions with alternative claims to antiquity.

To investigate these questions, we encourage the adoption of interdisciplinary perspectives fostering dialogue between intellectual history, cultural and classical reception studies and literary theory.

The following list of suggested topics is indicative (and not exhaustive):

- Articulating the couple Ancients / Moderns: historiography and temporalities, representations, imaginary

- A mediated relationship: from modern to ancient Greece via Western Europe. Introducing western European classical learning: translations and the policies of reception; The journey to Greece (itineraries, pilgrimages, travel guides);The mediation and cultural policies of foreign archaeological schools.

- Modern Greek institutions and the development of an ‘autochthonous’ classical scholarship: The Archaeological Society, the University of Athens, museums etc; National historiography and folklore studies.

- Antiquity in the light of the dominant political ideologies of the 19th and 20th century

- Antiquity and the Greek-Orthodox Church

- Antiquity beyond ancient Greece: Modern Greek perceptions of non-Greek ancient cultures (Roman, Jewish, Egyptian, Persian, et al)

- Antiquity in excess: Criticism and satires of the modern Greek obsession with antiquity; the discussion about kitsch

- Revivalisms: The modern Greek “parlêtre” or the insoluble language question; Material culture and Antiquity: Naming practices (first names, street names, names of plans of political repression or natural disaster prevention etc); Buildings (public and private); Symbols (coins, medals, stamps etc); Tattoos; Souvenirs c. Associations: Sports clubs, cultural societies, neo-pagan groups etc. d. videogames, comics, board games.

- Antiquity and sexual identities: The LGBT communities; homo-nationalism etc.

- The Antiquity of the Modern Greek DDiaspora: journals, associations, schools, restaurants etc.

The conference will take place at the National Hellenic Research Foundation on 24-26 September 2020. Proposals should be submitted in either French or English.