Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies, volume 4, nos. 2–3 (2016).

CONTENTS INCLUDE

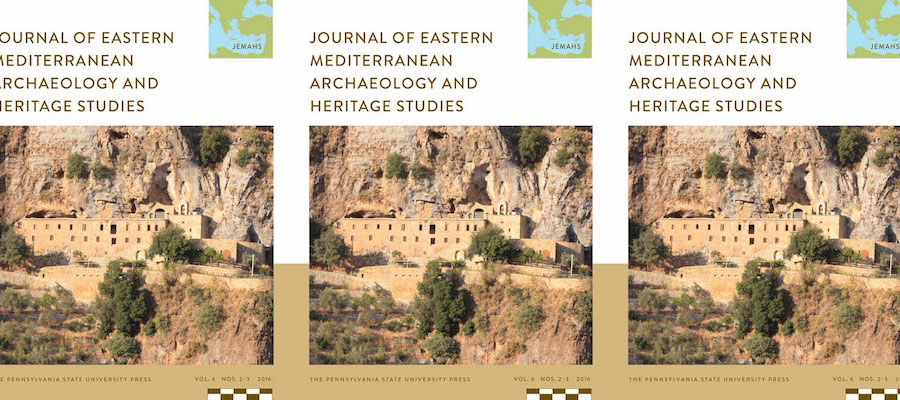

The Qadisha Valley, Lebanon

Anis Chaaya

The Qadisha Valley (also known as Wadi Qadisha in Arabic) is located in northern Lebanon and is one of the longest valleys in the Mount Lebanon range. It combines a beautiful unique landscape with numerous historical and archaeological sites. Carved out by the Qadisha River in a deep gorge, the valley is an oasis of peace, serenity, and spirituality for many. It has sheltered Christian monastic communities for centuries. The Qadisha Valley is an important area for early Christian monastic movements that have been coming to live and pray there since the fifth century AD, mainly the Maronite Church between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries. In 1998, the valley was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List as a cultural landscape.

Syriac and Karshuni Inscriptions on Wall Paintings in the Qadisha Valley, Lebanon

Gaby Abousamra

This article presents and discusses Syriac and Karshuni inscriptions on wall paintings in different monasteries, churches, hermitages, and caves in the Qadisha Valley in northern Lebanon. The Syriac language and script was used alongside the Karshuni (an Arabic language that uses the Syriac alphabet) and was spoken by many Christian communities at various times in this valley. Beyond the epigraphic analysis of these inscriptions, the aim of this article is to demonstrate that the different Christian communities living in the Qadisha Valley used the same places of worship throughout their long history.

Wall Paintings in the Qadisha Valley, Lebanon: Various Styles and Dates

May Hajj

This article offers a new approach to the study of paintings from four churches in the Qadisha Valley, Lebanon, including the paintings of Deir es-Salib and Saydet Qannubine, where a large part of the paintings are still in situ—albeit in a bad state of preservation; those in the church of Mart Shmuni, which were destroyed in the 1980s and are only known from photographs and the small fragments still visible today; and the paintings in the church of Deir Mar Asya, where the only remaining parts require immediate conservation. The focus here will be on the plaster used in these paintings, especially from the church of Deir es-Salib as it reveals many phases of intervention. Comparing the paintings and their iconography will also help define their styles and establish their dating.