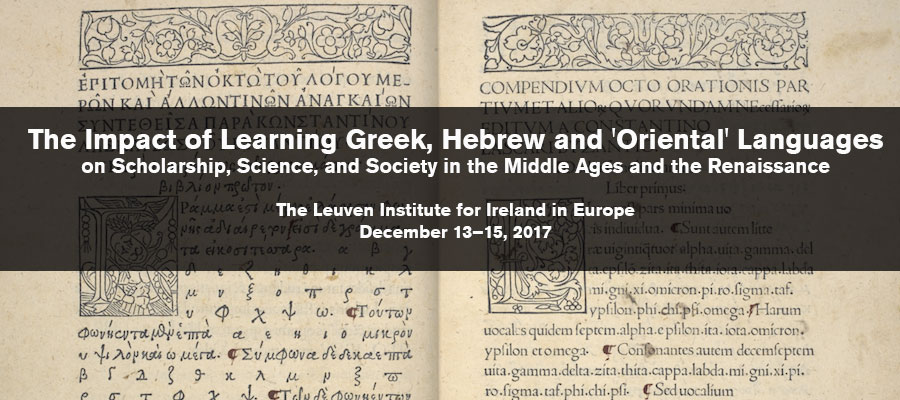

The Impact of Learning Greek, Hebrew and 'Oriental' Languages on Scholarship, Science, and Society in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, Lectio Conference, The Leuven Institute for Ireland in Europe, December 13–15, 2017

In 1517, Leuven witnessed the foundation of the Collegium Trilingue. This institute, funded through the legacy of Hieronymus Busleyden and enthusiastically promoted by Desiderius Erasmus, offered courses in the three ‘sacred’ languages Hebrew, Greek, and Latin. The initiative was not the only of its kind in the early 16th century. Ten years earlier, the first Collegium Trilingue had been established in the Spanish Catholic collegium of San Ildefonso, and similar institutes and language chairs were soon to follow. By the end of 1518, the university of Wittenberg offered courses of Hebrew, Greek, and Latin in the regular curriculum, whereas in 1530 king Francis I founded his Collège Royal in Paris after the model of the Louvain Collegium Trilingue. This fascination with Greek and Hebrew did not come out of nowhere, but had its roots in Renaissance Italy, whence it gradually disseminated to other parts of Europe. Moreover, it should be borne in mind that, as early as the beginning of the 14th century, the Council of Vienne had authorized and encouraged the foundation of professorships in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Arabic at four universities (Bologna, Oxford, Paris, and Salamanca), mainly in order to convert Jews, Muslims, and Oriental Christians to the ‘true’ faith. The council and Italian Humanism thus testify to the fact that enthusiasm for learning Greek and ‘Oriental’ (nowadays: Semitic) languages, next to Latin, among Western-European scholars and clergymen clearly predates the 16th century.

What is more, the Humanist connection explains why, even though the study of Greek, Hebrew, and other ‘Oriental’ languages was largely sparked by theological concerns, institutes such as the Leuven Collegium Trilingue reserved a prominent place for pagan (especially Greek and Latin) literature in their curricula as well. Moreover, also the special connection between the study of ancient Greek at institutes like the Collegium Trilingue and the legal practice and thought cannot be overlooked. In the early 16th century, indeed, Greek was the language of the new political and legal ideas. For jurist Reuchlin it was not an ancient language, but the tongue of Constantinople. Then, in the course of the 16th century, Greek culture was reduced to a pre-Christian culture because of its destabilization of Western Christianity, and to an old ‘democratic’ culture because of the influence of Greek imperialism on Western absolutism – a reduction to which also the Collegium Trilingue contributed. Hence, it weighted on legal studies, through professors as Puteanus, who wrote about law and politics. Law professors as Gérard de Courcelles had taught Greek at the Trilingue; Valerius Andreas had studied at this school; Tuldenus attached great importance to Greek literature as well. However, the Greek letters of the Louvain jurists had little to do with love of Antiquity. The study of the Greek language was neutral, and it allowed one to stay in touch with the heritage of Constantinople, which was slowly being absorbed into Western culture.

This year’s LECTIO conference will seize the 500th anniversary of the foundation of the Leuven Collegium Trilingue as an incentive both to examine the general context in which such polyglot institutes emerged and—more generally—to assess the overall impact of Greek and Hebrew education. Our focus is not exclusively on the 16th century, as we also welcome papers dealing with the status and functions accorded to Greek, Hebrew, and other ‘Oriental’ languages in the (later) Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period up to 1750. Special attention will be directed to the learning and teaching practices and to the general impact the study of these languages exerted on scholarship, science and society. We therefore look forward to receiving abstracts offering answers to the following questions, inter multa alia:

- What was the interrelationship between the Early Modern initiatives offering education in the three biblical languages, such as the 1508 Spanish Collegium Trilingue, the 1517 Leuven institute, the 1518 Wittenberg program, and the 1530 establishment of the Collège Royal? What is the connection, if any, between the 16th-century establishment of language chairs and the Late Medieval interest in these languages? To what extent are we informed about the teaching practices conducted in these institutes and universities, and about the learning of Greek and ‘Oriental’ languages in Western Europe before the 14th century? How did the institutes impact on university curricula?

- What significance was accorded to ‘antiquity’ and the classical tradition in the Colleges of the Three Tongues, in relation to the interest in biblical literature? To what extent can the confessionalization model be applied to the study of Greek and Hebrew in Catholic, Lutheran, and Reformed regions? Whereas the Council of Vienne clearly aimed at “propagating the saving faith among the heathen peoples” (Decrees, 24), the 16th-century humanists had for the most part much less explicit missionary goals with their study of ‘Oriental’ languages. What were their aims, and how did they strike out on this new course? What is the link, if any, with the several polyglot Bibles appearing in Europe in the 16th century?

- Despite the original hostility towards the polyglot institutes out of religious concerns, the study of Greek and Hebrew ultimately found acceptance rather quickly after about one generation, also among Catholic theologians. What circumstances explain and stimulated this process of acceptance? Who were the main protagonists and adversaries in it? Are there abiding differences among the various confessions in Europe regarding the degree they embraced the study of these languages?

- It is often argued that champions of Greek and Hebrew had to overcome several burdens. Not only did students of both languages risk to be suspected of heterodox beliefs, but they also had to surmount material hindrances, since only a minority of publishers were willing to invest in Greek and Hebrew font sets. To what extent can these claims be substantiated? What part did polyglot editions, such as those printed in Alcalà, Antwerp and Paris, play in this?

- How did the study of Hebrew and Greek affect the study and status of Latin? To what extent did the significance attached to both languages stimulate the study of vernacular languages and other ‘Oriental’ languages, such as Aramaic, Syriac, and Arabic? A number of scholars even felt confident enough to compose texts in Greek, Hebrew, and other ‘Oriental’ languages themselves: in what contexts and for what purposes did they do so?

- The study of Greek, Hebrew, and other ‘Oriental’ languages was often pursued by scholars interested in both law and sciences, such as medicine, biology, astronomy, and geography. How did the study of these languages impact on these disciplines and what was the concomitant societal effect? In what way, e.g., did Greek legal thought mark both the Protestant law faculties and the legal rationalism that originated in that world? How did Greek studies contribute to the Law Faculty’s renewed contacts with the Calvinist countries and enabled it to play a foundational part in the development of the legal doctrine, which Pufendorf would turn into ‘Natural Law’ in 1661?

The publication of selected papers is planned in a volume to be included in the peer-reviewed LECTIO Series (Brepols Publishers).